A remake is, by nature, an egotistical exercise. Choosing to revise and re-release an old work of art is looking back at it and saying, “You know what? I could do this better.”

Sometimes that turns out to be true. Sometimes it turns out to be horribly false. And sometimes, a release comes out that leaves you stunned, wondering what just happened and questioning the very nature of what it means to remake a video game. Must it be a graphical overhaul, faithfully recreating a classic work for modern sensibilities? Or can a remake be an opportunity to right old wrongs, to undo past injustices, to change the nature of your characters’ destinies?

Final Fantasy VII Remake, out on April 10 for the PlayStation 4, is a brand new video game wearing Final Fantasy VII’s skin. This remake is still a third-person role-playing game that blends fantasy with cyberpunk. It stars the same characters and explores the same events as the seventh and most popular mainline Final Fantasy, which was released in 1997. Yet this game is also an entirely different creature. For the bulk of its run time, Final Fantasy VII Remake is a glorious retelling of Final Fantasy VII’s story. It expands, tweaks, and fleshes out parts of the game that we’d previously never seen. It takes the first five hours of Final Fantasy VII—which make up about a tenth of the original game—and transforms them into a 40-hour extravaganza, with a new script, a new combat system, and all sorts of new characters.

Then it becomes something else entirely.

Days after finishing the game, I’m still trying to grapple with the consequences of Final Fantasy VII Remake’s ending, which will be heatedly debated in the weeks and months to come. It’s still not clear just what the developers at Square Enix plan to do next, but the ending makes it very clear that the project’s director, Tetsuya Nomura, has spent the past two decades as the chief creative behind Kingdom Hearts, the messiest and most complicated story in JRPG history. It’s also clear that Square Enix is aware of Final Fantasy VII’s massive cultural impact and wants to take advantage of that. This is an experiment that wouldn’t work with any other game.

It’s hard to elaborate without spoiling too much, so let me instead offer this: Final Fantasy VII Remake is a phenomenal game, one that any fan of the series should play. I’m not sure if people who haven’t played Final Fantasy VII will appreciate it as much or find the story all that comprehensible. But if you have at least a basic familiarity with the adventures of Cloud and crew, you’re likely to appreciate what is one of the most audacious remakes that we’ve ever seen in any medium.

In 2015, a few months after Square Enix first announced that Final Fantasy VII Remake was in production, they gave us all the catch: It’d be episodic. In the coming years, Square revealed that this first episode would only take place in Midgar, a circular, dystopian city run by an authoritarian energy company called Shinra. Midgar served as the introduction to the original Final Fantasy VII, letting you get to know characters such as Cloud, Tifa, Aerith, and Barret before they headed out into the open world to start the real game.

Although Midgar was a fascinating city—a disc-shaped icon to wealth disparity, in which the rich literally lived on top of the poor—it was always the appetizer to Final Fantasy VII’s main course. In the original game, your hero, the spiky-haired, aloof mercenary Cloud, was working for Avalanche, a group of eco-terrorists led by Barret, to fight Shinra. By the time you’d all left Midgar, the story had become something grander—a globe-trotting adventure to track down and fight the enigmatic villain Sephiroth before he summoned a meteor to destroy the planet. (You still fought Shinra, but they were a secondary concern.)

In Final Fantasy VII, the Midgar portion took four or maybe five hours to finish. News that Final Fantasy VII Remake wouldn’t leave the city was disconcerting, raising all sorts of questions. What were they doing? How could this feel like a complete game?

The answer is simple: Everything’s new. In what will surely be unwelcome news to Final Fantasy VII purists, this remake extends many old scenes and even brings in some brand new ones. The skeleton of the plot remains the same—Avalanche still blows up a couple of reactors; Cloud still meets the flower girl Aerith by falling into her church; your crew still invades Shinra’s headquarters—but the details are all different. It’s as if Final Fantasy VII were the outline of a school paper and Final Fantasy VII Remake is a grad school thesis.

In 1997, the streets and alleys of Midgar were portrayed through cluttered 2D backgrounds and stiff pre-rendered cutscenes; now they are part of a gorgeously realized city. In the original game, you had to let your imagination fill in many of Midgar’s blanks—the squalor of the Sector 7 Slums; the sleek, shiny suburbs on the plate above it; the way each map linked to one another. Now, you can see it all. What was once relegated to a fan’s imagination is now a city that seems to live and breathe.

Sometimes, abstraction is better than reality. It’s always tough for a game developer to surpass what’s been locked into a player’s brain after years of imagination. But Final Fantasy VII Remake’s Midgar is truly something to behold—a spectacle at which I could spend many hours marveling.

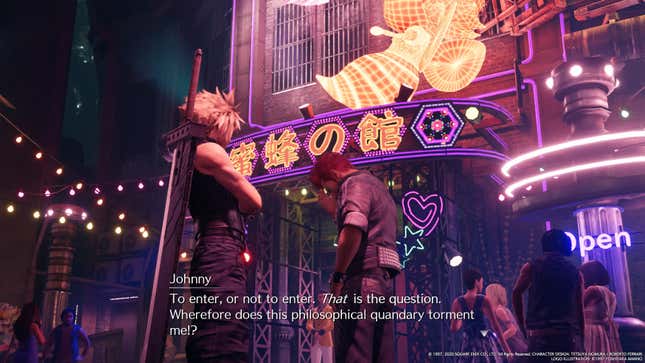

It isn’t just the city that’s built up and overhauled. Dialogue exchanges that took seconds to read in text bubbles in Final Fantasy VII are several-minute cutscenes in Final Fantasy VII Remake. Plot threads that were hinted at in Final Fantasy VII are now fully explored, while chunks of the old game that made no sense have been revised, like the Honeybee Inn, which in the original game is a bizarre brothel. In the remake, it’s something new—a highlight of the game that comes off as surprisingly progressive. (Who would’ve thought that a JRPG might talk about gender fluidity?) Enemies that were throwaway minions in the original game might suddenly turn into uber-bosses, while others might surprise you with fun mechanical twists.

Most importantly, Square Enix has finally fixed Final Fantasy VII’s English script. As former Kotaku producer Tim Rogers has described extensively, the original game’s English text was the victim of severe localization issues that led to mangled dialogue and a near-incomprehensible story for North American and European players. (That the game’s plot still resonated so strongly is a testament to the quality of everything else.) Final Fantasy VII Remake fixes that problem with panache, offering a charming script that rarely takes itself too seriously. There are some clunker lines in there—and the occasionally gratuitous cursing feels less like The Wire and more like a teenager at Hot Topic—but Final Fantasy VII Remake’s script is leaps and bounds better than the original game’s, delivered by a phenomenal cast of voice actors who very much seem to be having a good time.

You’ve gotta be impressed by the audacity. Here’s Square Enix, finally listening to thousands upon thousands of requests to remake Final Fantasy VII, and they’ve changed everything but the blueprint. It would have been far more straightforward to recreate the original game with brand new graphics—to transform the old blocky polygonal figures into beautiful models, retranslate the script, and overhaul the world while changing as little as possible. But Final Fantasy VII Remake isn’t all that interested in retreading old territory. In fact, this remake sometimes even flirts with deviating from the original game’s story, and although it never does anything as ballsy as, say, killing Cloud in the first act, Final Fantasy VII Remake does signal a level of self-awareness that I didn’t expect.

The changes aren’t all great. Dungeons that lasted a few screens in Final Fantasy VII—like the tunnel just before the Sector 5 reactor and the sewers beneath the city—can sometimes take an hour to finish, which gets tedious. Bosses that were over in 30 seconds in the original game are now hulking beasts or robots with unique weaknesses and multiple phases—sometimes satisfying, sometimes exhausting. The new side quests are mostly monotonous, and the mini-games (darts! Pull-ups! A coliseum!) can be fun but also feel like they exist to be items on a back-of-the-box checklist. I did enjoy the optional battles against summonable monsters from Final Fantasy VII, like the ice queen Shiva. Beat them in a VR simulator run by a Shinra intern named Chadley and you’ll be able to conjure these mystical beasts (and chocobos) during tough combat encounters.

Final Fantasy VII Remake’s new script and some added scenes flesh out characters who were previously nothing but faces and names—most notably, the Avalanche members Jessie, Wedge, and Biggs (voiced by returning Final Fantasy actor Gideon Emery, which can be a bit distracting—I just kept hearing Final Fantasy XII’s Balthier). In the original game, these characters were paper-thin and exited the story just as quickly as they entered. Here, they’re nearly as important as your main team. It’s far easier to empathize with the class struggle of Midgar when the people feel real—especially now that their faces actually have noses.

Fans might be baffled by the addition of some strange new characters—what, you don’t remember Chocobo Sam?—but they all serve either to help develop the main cast or to add life to Midgar itself. Only a couple of these new chunks of game feel superfluous, like one late-game sequence involving a Don Corneo henchman whose emotional arc is never quite as poignant as the game thinks it is. (He’s presented as an aloof pseudo-villain with a tragic backstory, but his personality is so stoic, he’s just boring.) Other scenes, like a chapter in which Cloud goes to the flirty, agonized soldier Jessie’s house and learns why she’s fighting against Shinra, are delightful additions to the story, enhanced by top-notch voice acting and stunning views of Midgar.

Final Fantasy VII Remake hints at old mysteries, giving Cloud plenty of hallucinations and flashbacks (much like the original game), while adding some fascinating new questions. Early in the story, your heroes are introduced to a group of dementor-looking spirits who appear and disappear throughout the game. Their identity is a big question throughout Final Fantasy VII Remake. The answer—and the resolution—changed my perspective on everything.

Sometimes, the goal of a video game remake is to make a game more palatable to modern audiences—to update the graphics, fix the controls, and get you playing it on whatever new Xbox or PlayStation came out most recently. Final Fantasy VII Remake is different. Final Fantasy VII Remake invites you to think about what, exactly, should be remade.

Take Aerith, for example. In one chapter of the remake, Cloud and Aerith scamper across the ruined rooftops of Midgar’s Sector 5 as they escape from a group of pursuing Shinra guards. In the original game, this is a cute little moment—10 seconds of flirting as Cloud teases Aerith for getting tired as they jump. In Final Fantasy VII Remake, it’s breathtaking.

Aerith is one of the most improved aspects of this project. In 1997, she was presented as a spritely ally, but the garbled English script lost many of her best lines. In the remake, she feels like a brand new person—a lively, spiritual florist who’s as comfortable cracking a joke as she is connecting with the planet. Final Fantasy VII‘s Aerith was charming—Final Fantasy VII Remake’s Aerith is a lovable goofball. The remake gives her more time to speak and to interact with the other characters, including some wonderful buddy-buddy scenes with Cloud’s childhood friend Tifa. Through those moments, you get a chance to get to know her in a way that the original English Final Fantasy VII never quite pulled off.

Or, take combat. Final Fantasy VII had random encounters and turn-based battles; everyone knows that. But was it something its developers wanted to include or something they felt compelled to add to the game because of technical restrictions? Was it just a Final Fantasy tradition to which they had to abide?

Combat in Japanese role-playing games started off as something of a metaphor. Memory restrictions on early video game hardware made it impossible to render every single enemy on the map, so they took place on a separate battlefield. Each of the first 10 mainline Final Fantasy games had invisible random encounters—as you were walking around in a dangerous area, the screen would suddenly shake, then transition to a battlefield screen on which your characters lined up opposite your enemies, each attacking when it was their turn.

Final Fantasy VII’s battles included some fun flourishes, like special victory poses for each character, but they mostly unfolded in the same way as the previous six games. Final Fantasy VII Remake says: Screw that. No more turns. No more invisible monsters. Technology has advanced past graphical metaphors.

Combat in this remake takes place in real time, much like Final Fantasy XV or Kingdom Hearts, against enemies you can see as you roam Midgar’s slums and tunnels. You hack away at enemies using short-ranged attacks for Cloud or Tifa and long-ranged attacks for Barret or Aerith, building up an “ATB gauge” (named after the classic Final Fantasy combat system: active time battles) that allows you to cast spells, use items, or execute special abilities. Your effectiveness in combat is augmented by your gear, your weapon upgrades, and your materia—small crystals that can be attached to weapons and armor to enable magic and enhance your abilities.

Spamming skills like Cloud’s uber-powerful Triple Slash will do you just fine, but the most efficient way to take out enemies is to stagger them. Staggering opponents, a mechanic adapted from Final Fantasy XIII, knocks them to the ground and paralyzes them for a few seconds while boosting your damage by a significant percentage (typically 160%). Different enemies in Final Fantasy VII Remake are susceptible to staggering in different ways. Some will just fall down when you do enough damage to them, or when you cast a spell targeting their weak point. Others require more unique strategies—one flying enemy, for example, will be more prone to staggering if you dodge their aerial attacks.

It’s a strong combat system that only occasionally drags during a bullet-spongey boss (there are oh so many robots with oh so many phases) or filler dungeon (did we really need more sewer levels?). The wrinkle is that you can only control one party member at a time. Whoever you’re not controlling spends battles standing around, occasionally hitting monsters but mostly waiting for you to order them to use spells or abilities. The goal of this system is ostensibly to make you feel like the main character is the one in command—characters even shout lines like “It’s my turn” when you switch to take control of them—but in practice, it just feels like your friends are idiots.

There are some ways to automate ally behavior, like a useful Auto-Cure materia that will make a party member heal anyone who’s in the red, but it’s not ideal. Some sort of rudimentary AI (or at least more materia like Auto-Cure) would have done wonders. As I played, I found myself badly missing Final Fantasy XII’s elaborate Gambit system, in which you can craft your own contingencies for each character (ie: “if you see an enemy, immediately steal from them”). Granted, that was a very different game, but Final Fantasy VII Remake’s ineffective party members feel like a regression.

It all makes one wonder: Is this better than turn-based combat? Is it worse? You won’t find yourself mindlessly mashing the attack button—as I have while revisiting the original Final Fantasy VII for comparison—but you might miss some of the more strategy-heavy aspects of the original game’s bosses. (The game’s semi-turn-based “classic mode” is a poor facsimile.) Warping to a new battlefield for each encounter and selecting options from a menu screen would have certainly felt antiquated alongside these cutting-edge production values, but it’s still fascinating to see a video game remake choose to completely overhaul its namesake’s core mechanic.

And Final Fantasy VII Remake’s production values really are impressive. The soundtrack, a brand new take on Nobuo Uematsu’s stirring original music, is full of straight bangers including some wonderful spins on the themes of characters like Aerith and Tifa. Some of the setpieces feel straight out of Uncharted, complete with death-defying leaps across falling debris. Midgar is as beautifully gritty as anyone might hope, and this remake offers a close-up perspective that helps you see the city’s class struggle more intimately.

During one sequence, late in the game, as you climb one of Midgar’s pillars in hopes of reaching Shinra’s headquarters in the center of the city, the views are hard to believe. Over the past two decades, plenty of fans have tried to imagine what a complete 3D remake of Final Fantasy VII might look like. Aesthetically, this game surpasses even the loftiest of expectations, aside from a few quirks.

There are texture loading issues, for those who pay attention to that sort of thing, which can lead to some weird-looking doors and walls. There’s also a persistent, annoying audio glitch that cuts off characters’ voices when you’re not facing them as they talk. During battle, some of the stock lines of dialogue can get grating, although I did enjoy hearing Barret yell “Asshole!” at a Fat Chocobo.

Final Fantasy VII Remake ran at a steady framerate on my launch PS4, and although the console sounded like a jet engine, I didn’t mind. I just cranked up the volume. Midgar was calling.

For the past few years, I’ve been loudly cynical about the nature of the Final Fantasy VII Remake project. I’ve been skeptical of the decision to break this game up into episodes, and was especially worried when we learned that the first game took place solely in Midgar. After all, I’ve played Final Fantasy VII half a dozen times. Midgar is burned into my memory. How could they possibly make an entire game out of that four-hour sequence?

Playing through Final Fantasy VII Remake, then, was a surreal experience. As I fought through endless waves of Shinra soldiers and helped do chores for the residents of Midgar’s slums, I felt in some ways like I was going through the motions. Okay, just got off the train—now we go to Sector 7. Then it’s time to blow up another reactor. And so on. And so on. Even as I enjoyed the new cutscenes and marveled at the sights and sounds of Shinra, I always knew what was coming next. Cloud’s fall. Wall Market. The train graveyard. The big escape. It’s a weird feeling, playing a game that feels brand new yet utterly predictable at the same time.

I marveled at the small moments—the challenging fights, the lovely dialogue exchanges, the explosive new set-pieces. I spun around the camera and tried to take in all of Midgar’s sights and sounds. Final Fantasy VII Remake is unquestionably a good video game, and on a moment-to-moment level, I was really enjoying it.

But I was also confident that by the end of it all, I’d feel unsatisfied. Every flashback to Cloud’s razed hometown of Nibelheim or hint about Sephiroth’s clones joining together for Reunion was just a reminder that we wouldn’t actually see those scenes in the game. Every new character or extended dungeon felt like it was taking away time that could have been devoted to chunks of Final Fantasy VII that I knew wouldn’t be in here, like Junon, the port city built around a giant cannon that you visit shortly after Midgar. I wanted to see Final Fantasy VII Remake’s take on the beach resort Costa del Sol, or that glorious flying theme park, the Golden Saucer. I was prepared to burst into tears at… well, I won’t ruin that one thing. (You probably know the thing.)

Then I got to the end and realized that, without spoiling anything, the game’s developers were more or less asking what it means to remake a video game. How faithfully do you have to stick to the script? Just how much, if anything, do creators owe their biggest fans, the ones who have spent so many years begging for a release like this?

By the time I reached the credits, Final Fantasy VII Remake had left me simultaneously thrilled and confounded. I still want to see the rest of the game, but, taking in the sweep of things and noticing the cumulative effect of a succession of surprises, I think I understand what the developers are trying to do—and why it had to be presented and released this way. The answer, of course, is that a remake can be whatever its creators want it to be.

Final Fantasy VII Remake is not what I expected. It’s a grand, ambitious, beautiful experiment, a bold new take on a game that millions of people remember fondly. It sometimes feels shackled by the weight of two decades worth of expectations, but it handles those restraints with aplomb. I certainly can’t wait to see what’s next. As a great man named Barret Wallace once said: There ain’t no getting off this train we on.